This story is syndicated from The Columbia Spectator, the newspaper of Columbia University in New York City. The original version of the story ran here.

In interviews with Spectator since the complaint was filed, 16 current and former employees of the Department of Public Safety and Facilities and Operations corroborated many of these claims. Their stories painted a bleak picture of a department shrouded in secrecy that has lost some of its highest-ranking leaders in recent years. The employees attribute the environment to alleged bullying by Deidre Fuchs, a department veteran of 17 years who rose through the ranks to the department’s top job last year.

The employees—who ranged various levels of professional experience, races, and genders—spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation. As one put it, Fuchs “not only had power in this department, but she had it outside of this department.”

“She still holds a lot of power and influence on a lot of people,” the person said.

Photo by Kat St. Martin

In an incident in October, Fuchs referred to one less senior employee as a “cockroach,” according to two people familiar with the incident. She called another a “short motherfucker,” the two people said. She also allegedly disparaged Gerald Lewis, the new vice president who replaced her several months ago, they said.

It was not the first time, according to eight people, she bullied employees who lacked the power to fight back.

“A toxic workplace culture exists within the Department of Public Safety,” the September complaint said. “The members of Public Safety desperately need help.”

Photo by Judy Goldstein

When Fuchs first came to Columbia from the New York Police Department in 2006, she left amid a controversy.

Her job was an important one. As a detective in the detail of former NYPD Commissioner Raymond Kelly, she received a master class in the cutthroat acumen needed to survive among New York City’s top law enforcement brass.

When then-NYPD Captain Eric Adams retired that same year, with his sights set on state office, Kelly had filed insubordination charges against him.

Around that period, Fuchs was one of a number of other employees to leave Kelly’s detail. Several years prior, James McShane, a deputy NYPD chief who worked with Fuchs, had left for a position at Columbia, where he became vice president of Public Safety in 2004 until he retired in January 2022.

It was not long before McShane recruited Fuchs to Columbia. She started out in the department’s administrative and special operations and events units and, by 2014, was promoted to lead the University’s investigations team. Such units are common on college campuses and are typically in charge of probing and preventing crimes.

“The Investigation Unit utilizes the latest technology to ensure thorough and successful investigations within the Columbia community,” the University’s most recent safety report, which is required by federal law to be publicly released each year, says.

The two worked closely together for almost two decades and led hundreds of employees. Fuchs became a “fixture” of the department, David Greenberg, executive vice president for Facilities and Operations, wrote in an internal email in November.

With her help, McShane navigated the challenges of the University’s expansion uptown. A nascent team took shape to secure the Manhattanville campus.

The department dealt with high-profile tragedies, too. Barnard first-year Tess Majors was stabbed to death in Morningside Park in 2019. A few years later, doctoral student Davide Giri suffered a similar death near Morningside Park. Both incidents revived dueling debates over increasing safety amid calls for police reform.

At the same time, trouble was brewing in the department’s highest ranks.

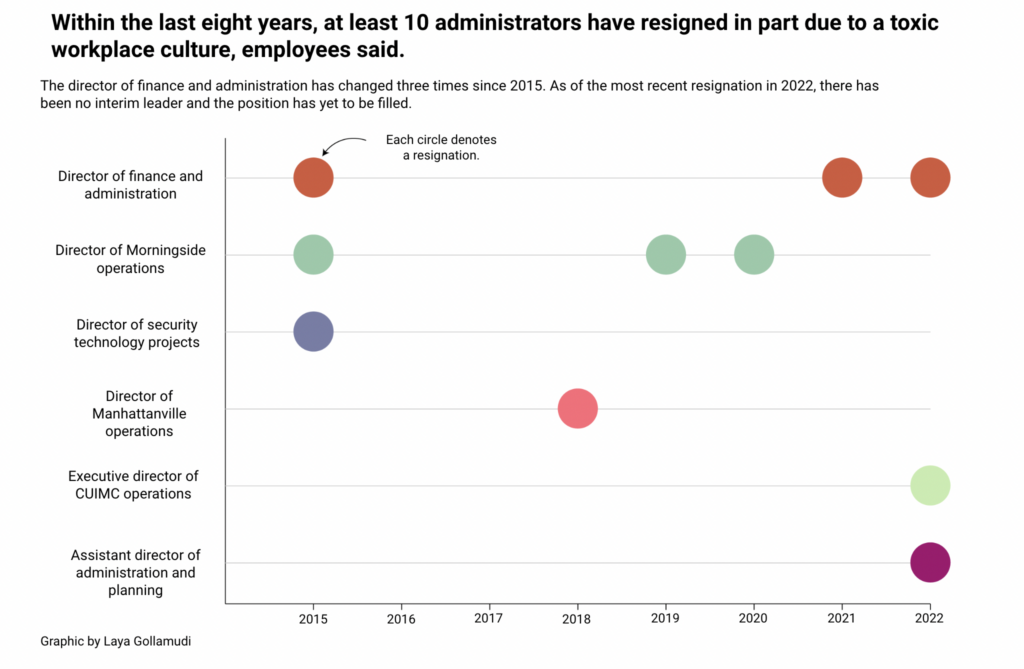

In 2015, Fuchs’ “management style” led to the departure of three people in the executive management team, according to the internal complaint and eight people familiar with the situation. Three years later, another major resignation slid under the radar. Then came five more.

There have been at least 10 departures from executive management positions since 2015, largely due to the workplace environment, per the complaint and the eight people.

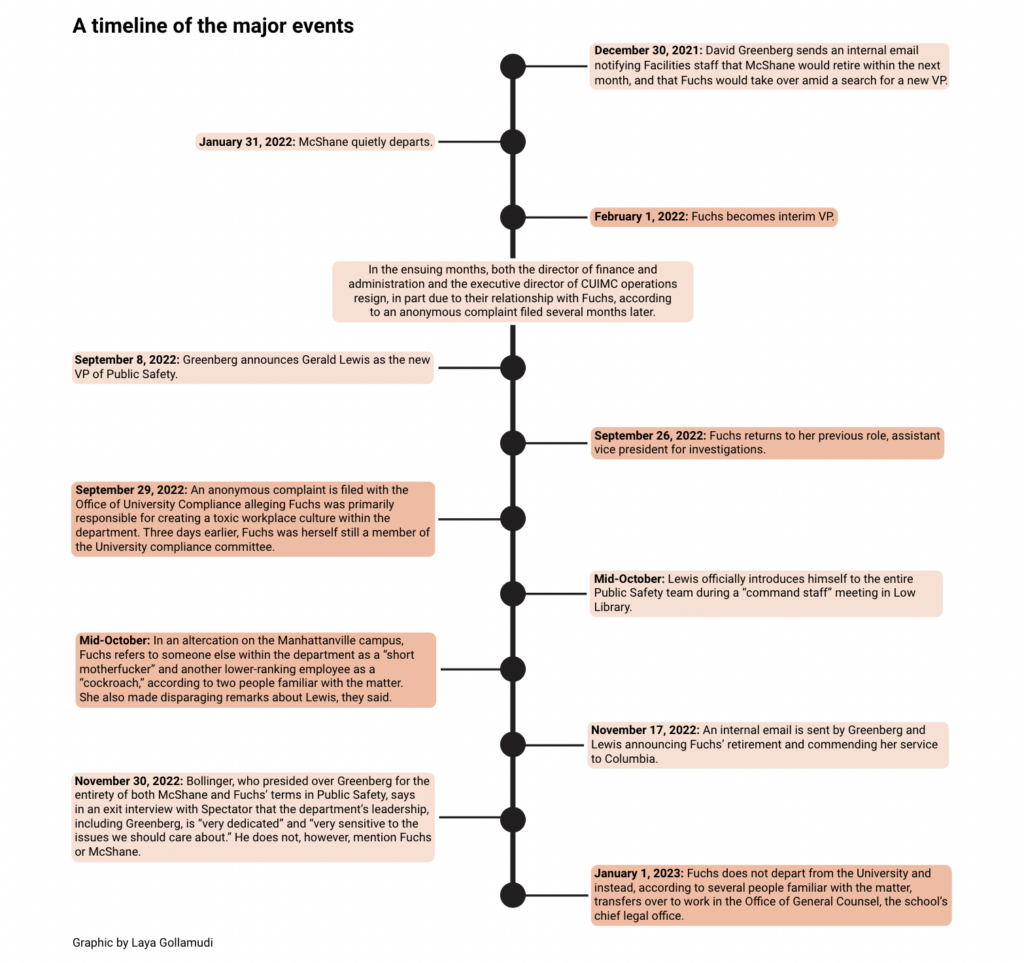

When McShane quietly retired last January, Greenberg tapped Fuchs to take the top job until the department could find a replacement. In an interview with Spectator last February after Fuchs took over, Greenberg said Fuchs had the department’s “full backing.”

She held the post for about eight months, as the search for the next vice president happened largely behind closed doors. The search committee eventually landed on Gerald Lewis, the University of Connecticut’s police chief, to replace her. He took over in late September.

After a couple months with Fuchs back in her old role leading investigations, Greenberg and Lewis penned an internal email in November announcing that she would retire by the end of the year. The announcement, which praised Fuchs, came a couple months after the September complaint.

Whether the complaint and the retirement are related is unclear.

“Long a trusted partner and advisor to colleagues across the University, Deidre would always quickly return a call or email and would go the extra mile to help, even when the requests were outside her responsibilities as would often be the case,” Greenberg and Lewis wrote. “Her contributions to Columbia are felt across the University.”

Nearly all the current and former department employees and people who Spectator interviewed said her authority stretched too far. Eight people who worked directly with Fuchs said the alleged behavior included unethically abusing the surveillance tools at her disposal to harass and intimidate people she did not like. It caused waves of strife among certain teams in the department, they said.

They said things reached a boiling point over the past year when Fuchs’ alleged targeting partially caused the director of finance and administration and the director of operations at the medical center to leave, according to the complaint. The first position is still vacant.

The people said Fuchs created an environment in which many employees felt like they were “walking on eggshells” every day. She routinely berated less senior employees, including by using derogatory language to their faces, yelling at them, and aggressively micromanaging them, they said.

The alleged targeting left some employees sick—both mentally and physically, according to eight people.

Meanwhile, Fuchs’ bosses were aware in some fashion of the situation, current and former employees said.

Three people familiar with the matter said Greenberg was directly informed of management problems stemming from Fuchs. Though it is unclear exactly how much Greenberg knew about the situation, he worked with Fuchs and McShane for many years.

Another person who worked with Fuchs said a human resources investigation was conducted into the investigations unit several years ago. At the time, HR investigators asked a number of department employees about a toxic environment in Public Safety’s investigations unit and asked specifically about Fuchs, he said.

The person said department employees were told not to notify Fuchs about the probe. But she already knew, he said.

Another person familiar with the matter said Dan Driscoll, who has been the head of HR since 2017, is also aware of Fuchs’ alleged targeting.

When Spectator asked the University about these allegations, a spokesperson mostly declined to comment on the record. She referred Spectator to the internal email announcing Fuchs’ retirement.

Through the spokesperson, Fuchs declined to comment. Greenberg and Driscoll also declined to comment. McShane could not be reached for comment.

In an interview with Spectator in November, University President Lee Bollinger called the department’s leadership team “very dedicated.”

He said its leaders, including Greenberg, have been “very sensitive to the issues that we should care about.”

Photo by Violet Mendelsund

‘An entire overhaul’

A Spectator investigation over the course of several months uncovered persistent allegations of a power structure in the department that has valued loyalty over a healthy workplace environment. For years, employees have feared retaliation if they raised concerns about their superiors, particularly about Fuchs, as they say they watched others face repercussions.

Places like the Office for Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action and Columbia Human Resources were “not safe,” one employee said.

“Everyone is afraid to speak,” he said.

The environment has driven some of Public Safety’s most dedicated people away over many years, current and former employees said, while the employees Fuchs favored rose through the ranks.

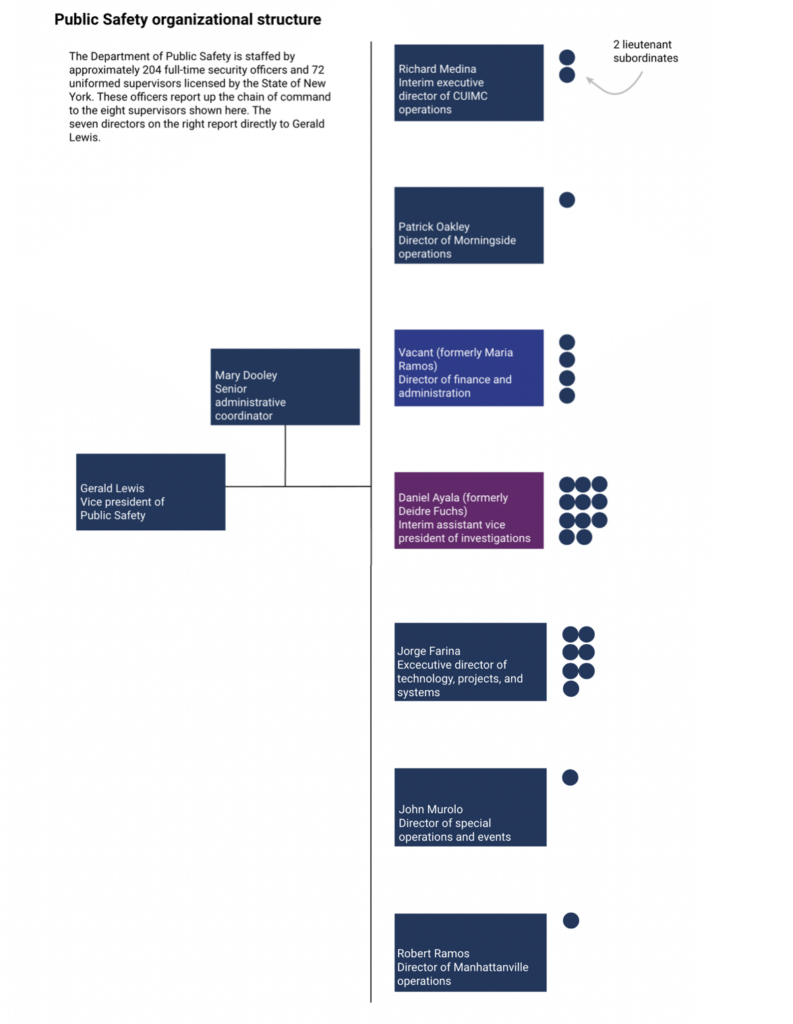

Many of the employees they claimed she favored still hold nearly all of the department’s highest-ranking positions. Almost every person currently sitting in the department’s top seven jobs, excluding Lewis, was appointed by Fuchs or is close to her in some way, two employees said.

Graphic by Tajh Martin and Adina Cazacu-De Luca

Those who could not get along with her left, even though many of them loved Columbia, the people said. If not for the workplace environment, which they widely considered to be toxic, many would have stayed.

“I can name probably 30, 40 names that left because of one person,” one employee said, referring to Fuchs.

While Lewis’ appointment has sparked some hope about the future, the people said Public Safety’s challenges were never confined to just one leader.

“The way that she ran things was one of the biggest problems,” another employee said. “But it’s a much bigger problem than just Deidre. The whole culture of the Public Safety department, it just needs an entire overhaul.”

‘Very Concerning’

Public Safety’s investigations team has a broad mandate, and its employees are not necessarily bound by the same rules and laws as detectives in police departments.

One of the team’s main roles is to follow up on all reported crimes, according to the University’s annual safety report.

“The investigators provide assistance and coordinate with local law enforcement, if necessary, and use video technologies in the investigation of cases,” the 2022 report states. “Our investigators have years of experience, integrating traditional investigative techniques with up-to-date technologies.”

The unit also works closely on cases with the Office of General Counsel, Columbia Human Resources, the Office of Student Conduct, and the Office of Gender-Based Misconduct, according to the report and University policies.

One reason why the team holds a lot of authority on campus is because Public Safety is the sole department authorized to have full administrative rights to CCTV, the University’s video surveillance system.

According to the University’s official CCTV policy, only the vice president for Public Safety—or someone of their choosing—can determine which Public Safety employees can have access to surveillance data. And only the investigations director, which has been Fuchs for years, can authorize anyone outside of Public Safety to see it.

When the NYPD subpoenas the department for video footage, the policy states, investigators work closely with the Office of General Counsel to hand it over to the city.

The policy promises that “video monitoring and recording for safety and security purposes will be conducted in a professional, ethical, and legal manner.” It requires recording and monitoring to be done in a way that “respects the reasonable expectation of privacy among members of the community.”

Eight current and former department employees said it has been anything but.

They said Fuchs and others have used the system to improperly conduct surveillance on members of the Columbia community, mostly on other Public Safety employees, without having opened an official investigation into them. The University’s official policy says CCTV “may only be used to monitor and record for legitimate safety and security purposes.”

Daniel Carter, a campus safety consultant and president of the consulting agency Safety Advisors for Educational Campuses, said if true, such conduct would be concerning. He made clear he could not speak to the truth of the allegations, but agreed to give his opinion on the alleged behavior.

“I would say it’s very concerning to have Department of Public Safety personnel essentially spying on other personnel,” he said in an interview.

“That’s an improper use of University resources, if nothing else,” he added. “It takes away from the work they’re supposed to be doing to keep the campus safe, and that’s in addition to any other ethical considerations.”

Photo by Salem Maru

‘Extremely Intimidating’

Fuchs “had people listening and recording all the time,” a former department employee said.

That employee—who was also an undergraduate student at the time—said Fuchs targeted him in 2019 after he asked her about the recent turnover within the department.

His questions angered Fuchs, according to him and the September complaint, and she reportedly informed the rest of the executive management team in a meeting she would find a way to fire him.

He was “surveilled over the course of weeks at great expense,” according to the complaint.

“She routinely utilizes the LENEL and CCTV system to conduct surveillance on members of the department and the Columbia Community by tracking their movements via their CUID card swipes,” it states. “She does this routinely and without justification or provocation.”

The incident culminated in a tense exchange in her office, he said. Fuchs and two senior investigators allegedly accused him of stealing time from the University for clocking into work remotely. They showed him surveillance footage and swipe logs, he said.

The student said neither he nor his predecessors were always expected to work around the clock in person. According to the complaint, all of his timesheets had already been approved. No one had raised any concerns about them, he said, or filed any sort of grievance about him.

Still, Fuchs called him a “thief and a liar,” the complaint states. He said she later told him if he were more competent, he would not have gotten into the situation in the first place

“I was surrounded by these senior former NYPD officers who had me cornered in this office,” he said.

He called the experience “extremely intimidating” and a “completely inappropriate way for a University administrator to speak to an employee, let alone a student.”

Photo by Millie Felder

‘Sh*t List’

For years, everyone knew it was important to stay on Fuchs’ good side, a former employee said.

“Once you’re on her shit list, it’s over for you,” he said.

Letting a call go to voicemail, taking time off, or having some form of medical-related absence could invite her ire, they said.

“It just took for me to have one disagreement with her and not allow her to berate me,” the employee said. “And then everything changed.”

From that point forward, that particular employee said every part of his work life—from where he was physically stationed to his day-to-day schedule—became different.

After an initial incident, the alleged targeting would often escalate, another employee said. Small mistakes or attempts to raise concerns would land subordinates in her office; those situations were known to involve yelling and derogatory language, eight people said, including by calling employees stupid and incompetent.

A former lieutenant described one such situation from several years ago.

“I’m a grown man, and I left that office in tears,” he said.

It got to the point where some employees were getting sick and would have to leave, according to another employee.

“Like physically sick,” he said.

‘The problem’

The alleged bullying is an example of the type of power-based harassment Columbia has historically struggled to address, despite multiple systems in place that are supposed to handle it. One of those systems is the Office of University Compliance, which received the September complaint.

Until a few days before it was filed, Fuchs herself, as vice president for Public Safety, was a de-facto member of the University compliance committee—though that changed as soon as Lewis, the new vice president, took over. The committee is responsible for overseeing the implementation of the compliance program throughout the University.

Administrators and faculty are currently trying to set in stone a University-wide definition of bullying, which some of Columbia’s peer institutions have already done. Recommendations from last year proposed setting up a new Office of Conflict Resolution. If approved, the OCR would be a central place for addressing this type of conduct across Columbia.

But University leaders do not seem to be looking specifically in the direction of Public Safety. The effort was instead sparked mostly as a response to union demands. Postdoctoral students nationwide, for example, are often disproportionately vulnerable to power-based harassment, as evidenced by a recent union survey.

[Read more: Postdoc union alleges University broke contract through exclusion of journalism, law postdocs]

In September 2021, University Provost Mary Boyce convened an anti-bullying task force to address the issue. Donna Fenn, the associate general counsel who has had a close relationship with Fuchs, according to several people, was a member of that group. Through a University spokesperson, Fenn declined to comment for this story.

Fenn is also an ex-officio member of the Inclusive Public Safety Advisory Committee, a group formed a year ago by Bollinger with the goal of providing “guidance to Public Safety on how to enhance their practices and policies and further foster an inclusive and equitable campus community.”

Until recently, Fuchs was an ex-officio member of that committee, too.

‘The report’

Two external consulting firms—Teneo, a management consulting company, and Margolis Healy and Associates, a professional services firm—were quietly brought in to examine the work environment at Public Safety. Over the course of several months throughout the fall, employees across the department were interviewed by outside investigators. It was not entirely clear what prompted the review, though it came on the heels of both Giri’s death and McShane’s departure.

The firms requested a trove of information from the department, including staffing schedules, internal memos, the resumes of department leaders, and the budget for the last two years. They also asked for a copy of Columbia’s memorandum of understanding with the NYPD, as well as all service calls the University has made to the NYPD since 2020.

Several people who were interviewed for this story said they were specifically asked about a toxic workplace environment, and whether Fuchs played a role in it.

A final report was supposed to be delivered to a small group of senior administrators in the first quarter of this year, according to two people familiar with the matter.

The University has not publicly acknowledged the external review. But a person familiar with the matter said its findings have been shown to senior administrators.

When asked several times if the University would commit to releasing the findings publicly, a University spokesperson declined to comment.

Adding to questions about the report’s findings, Fuchs’ employment status at the University remains unclear. Though her retirement was communicated internally months ago, a person familiar with the matter said rather than leaving Columbia, she transferred to the Office of General Counsel on Jan. 1. A University spokesperson said Columbia does not comment on personnel matters.

Regardless, Lewis’ arrival amid Fuchs’ departure has marked perhaps the biggest substantive leadership transition the department has seen in years. For some, that brings hope. And they think the changes are not over.

“It’s the most light at the end of the tunnel we’ve ever seen,” one said.